Part legend, part myth, part enigma, Hang Tuah has loomed large in the Malaysian imagination for centuries. The 15th-century Malay warrior is celebrated in the Hikayat Hang Tuah as a paragon of loyalty and skill, his name etched into school textbooks, street names, the arts, and the national narrative.

Yet beyond these official frames, Tuah remains unsettled.

To some, he was a hero whose unshakable fealty embodies the ideals of loyalty and service; to others, he is a symbol of obedience to power, even at the cost of justice. Still, others see him as a ghost from a distant past, more story than history, whose existence is debated and whose meaning shifts with each retelling.

It is in this charged space that Fragments Of Tuah by Five Arts Centre enters as a new documentary theatre work set to original music.

It is set to play at the Kuala Lumpur Performing Arts Centre from Aug 28 to Sept 7.

First produced as a video essay in 2022, Fragments Of Tuah is a culmination of three years of explorations and examinations into the many ways Hang Tuah has been imagined, reinterpreted, and debated across history and into the present day.

“Over the past five or six years, I noticed a lot of attempts to definitively prove that Tuah existed. This was especially during the Covid-19 years, which were marked by widespread anxiety and insecurity with so much time spent online. Somehow, this period accelerated the stories and even conspiracies of Hang Tuah,” says Mark Teh, Five Arts Centre member and director of this new 75-minute long theatre work.

“I wondered why these attempts were reemerging now, and against what backdrop. So I began to pay attention and to listen to the different efforts and attempts to prove that Tuah truly existed,” he adds.

Politics of storytelling

Teh points out the proliferation of materials and narratives that have arisen, including assertions about Tuah’s birthplaces, death sites, and burial tombs. These contentions are not just found in Malaysia, but also across the archipelago.

“So we began by tracing Tuah’s appearance across our landscape, including roads, stadiums, shops, and buildings. And the more we looked, the more we began to think about our relationships with this national icon,” says Teh.

Regardless of his historical existence, Tuah gradually became a national hero, often overshadowing real historical figures in symbolic significance. The placement of Tuah’s sculpture at the National Museum speaks volumes about this carefully constructed positioning around the contested figure.

For actor Faiq Syazwan Kuhiri, who carries much of the story, examining Tuah in this theatre work was a challenge.

“I took a more critical stance toward the subject. Because to slice open the figure of Tuah requires self-criticality of the idea of being Malay, and what that means. So there’s a discomfort in doing that,” says Faiq.

The process of creating the work echoed the ambiguity that surrounds Tuah. When Teh first approached the production team, each member brought different levels of interest, disinterest, knowledge, and even resistance to the subject.

For Wong Tay Sy, close collaborator and production designer, the initial response was hesitation. It was only after reading Hikayat Hang Tuah that her perspective shifted.

“The more I read, I realised that all I had was an impression of Tuah from other people’s interpretations. There are more nuances and complexities to what we’re taught or told. I realised that I did not know this guy at all. I also found familiar place names in the text that still exist in Melaka today,” says Wong.

“Because I am from Melaka, that connection was grounding – if he did exist, he would have walked the same tanah that I am now stepping on,” she adds.

For Syamsul Azhar, lighting and multimedia designer and Five Arts member, Hang Tuah is both fascinating and politically charged.

“I think he’s an interesting mythical subject. There are so many stories about him, and people are pushing for him to be real. Through research, I have seen how this subject has been used to push for supremacy and power.”

These responses underline how Tuah resists a singular interpretation, embodying contradictions and projections all at once. Such tensions point to why revisiting him remains a potent way to probe questions of history, identity, and power.

Remembering and resisting

Tuah straddles two worlds: the Hikayat Hang Tuah, and the Sejarah Melayu, where Tuah appears only as a side character.

Teh reflects on the evolving narrative, noting that in the former text, Tuah’s story extends far beyond the Malay world: “If this figure existed, he would have been contemporaneous with figures like Cheng Ho and Vasco da Gama”.

This positioning invites a fascinating reflection on Tuah, that beyond the fatal stabbing of Hang Jebat, he also took on diplomatic roles, straddling local legend and broader historical currents.

What adds complexity is the Hikayat Hang Tuah manuscripts themselves.

“There are like 20 of them all around archives in the world,” explains Teh, “... and they were all copied by hand.”

These unknown copyists exercised considerable creative license, introducing slight variations, editing passages, and adding new endings.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, print culture began to influence these texts, but the stories stopped evolving before the Japanese occupation during World War II.

Teh sees this continuous editing, alongside modern folk tales, speculations, and online conspiracies, as “all part of the same line, or same work”.

The award-winning director describes Tuah as “some kind of composite of different figures and folktales put together”, a collage that has become an iconic figure deeply embedded in the national and cultural landscape.

“Through our research, we realised that Tuah’s meaning is never stable, but constantly reconfigured. In the 1930s and 1950s, he was positioned as a central figure in national building, but that continuity to today is far from neat.”

In recent years, there have been renewed efforts to anchor his existence and cultural memory, often from disparate directions. Claims surface about artefacts from places as far-flung as Okinawa (Japan), India, and Istanbul in Turkiye, while earlier characters like Jebat have faded from the narrative altogether.

Many of these interpretations cluster around the second half of the Hikayat, where Tuah’s travels carry Melaka, and by extension Malaysia, out into the world.

Mirroring cultural values

Yet even this is read in a sharply nationalistic frame, reinforcing the ambiguity of whether Tuah belongs to history, to myth, or to ideology. Fragments Of Tuah thus traces this shifting discourse, capturing how Tuah continues to be shaped, used, and reinterpreted over time.

In this performance, the weight of the narrative is mostly carried by Faiq, who walks audiences through the different afterlives of Tuah, threading a range of fragments, including excerpts of Tan Sri P. Ramlee’s pre-Merdeka film, to strange rabbit holes of the Internet.

Because Tuah’s story has always existed somewhere between fact, myth, and invention, Faiq’s shifts in storytelling remind us that every version is partial, and every retelling is provisional.

Each scene moves in mode, sometimes poetic, sometimes documentary, inviting the audience to sit with uncertainty and multiplicity.

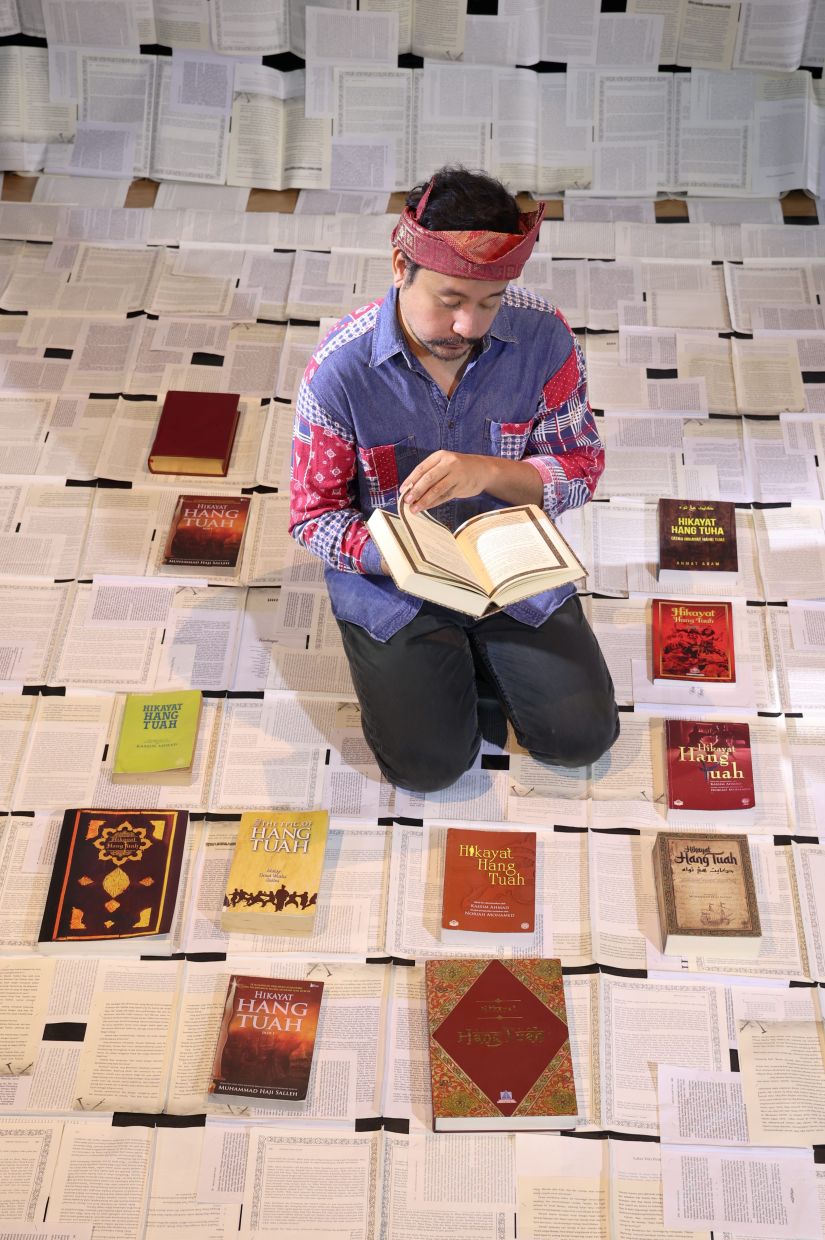

Co-creating this atmosphere is Wong, who works with the different manuscripts, versions, and translations, mixing and matching all available editions to reveal the tensions and slippages between them.

Syamsul captures the textures of this ambiguity while supporting moments of clarity through lighting and multimedia.

What emerges is less an act of recovery than a practice of reflection, remembering Tuah as a mirror of cultural values, shifting terrains, and contested narratives.

At the same time, there is resistance, an insistence on recognising how stories like Tuah’s are weaponised, romanticised, and mobilised for power.

To engage him, then, is to enter into the politics of storytelling itself, where remembrance and resistance are never opposites but intertwined gestures.

Fragments Of Tuah is showing at Pentas 2, KLPac, Sentul Park in Kuala Lumpur from Aug 28 to Sept 7.